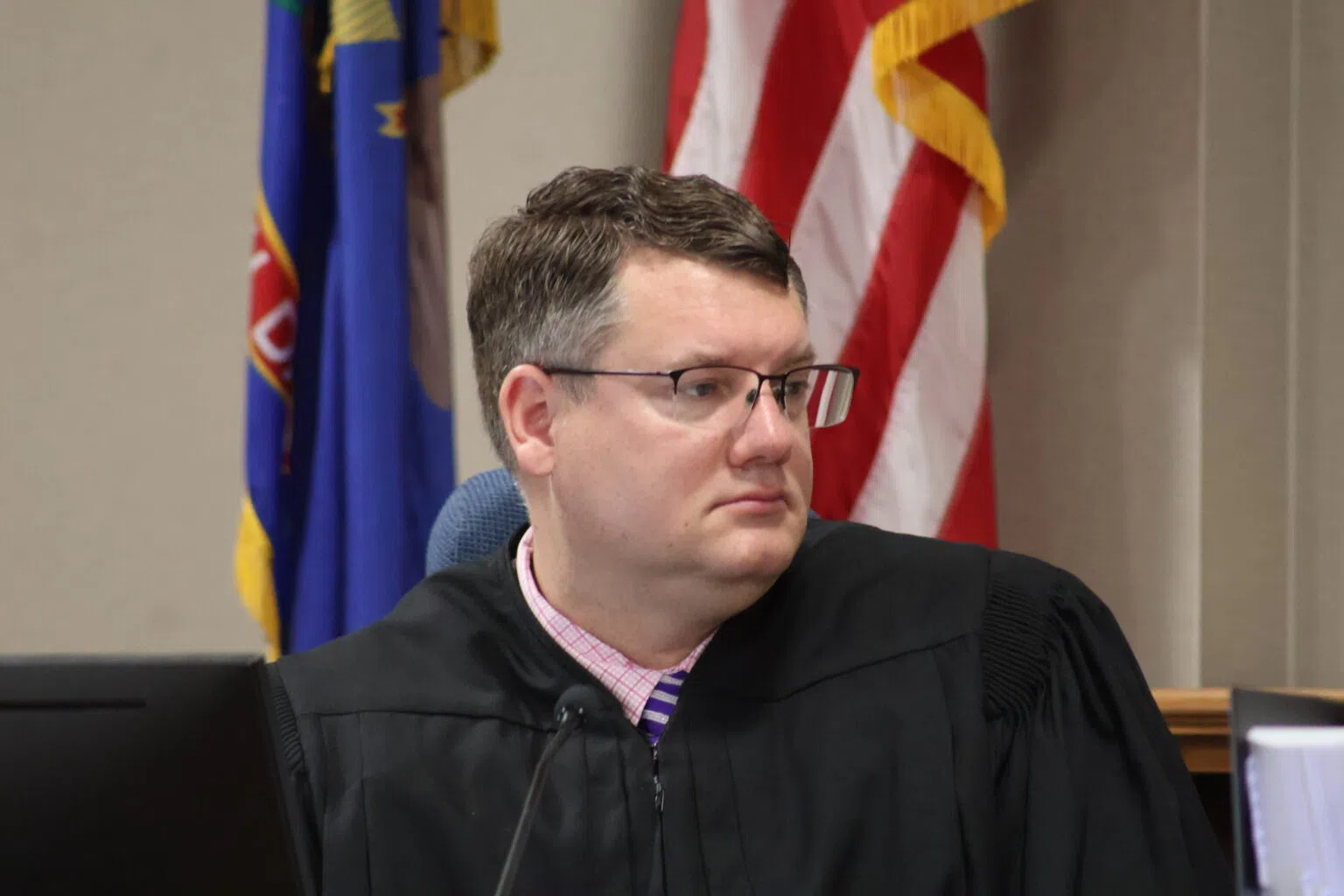

South Central Judicial District Judge Jackson Lofgren presides over a trial to determine the constitutionality of North Dakota’s ban on gender-affirming care for minors on Feb. 3, 2025. (Mary Steurer/North Dakota Monitor)

BISMARCK (North Dakota Monitor) — Testimony from kids and parents affected by North Dakota’s ban on gender-affirming care for minors wasn’t central to a judge’s decision last week to uphold the statute.

Instead, the ruling hinged on defining who deserves special legal protections and whether the law discriminates on the basis of sex, according to one state constitutional law expert.

The plaintiffs argued that transgender adolescents affected by the bill should be considered a protected class under the law because they are a small minority being forced to conform with government-imposed sex stereotypes.

Quinn Yeargain, an associate professor of law at Michigan State University, agreed, citing the history of discrimination against transgender people in areas like employment, health care and a host of other areas.

“It’s very difficult for me to conclude that transgender status, gender identity, however we want to label it, is not a protected class,” Yeargain said. “There’s every reason to believe that it is.”

Had South Central Judicial District Judge Jackson Lofgren agreed, the state may have had to work harder to prove the law is constitutional, Yeargain said. But Lofgren felt differently.

As he notes in his opinion, special legal status is typically granted to groups that are politically powerless and have repeatedly faced legal oppression. Courts have also found that an important characteristic of these protected classes is that they’re based on innate, unchangeable qualities — like race and ethnicity.

He rejected the notion that transgender people are politically powerless, pointing to the fact that many people testified in opposition to the health care ban and that other state legislatures and courts have acted in ways that bolster transgender rights. He also wrote that he didn’t see convincing evidence that the Legislature adopted the law out of animus toward transgender people, or that the authors of North Dakota’s constitution were aware of or supportive of transgender people.

Furthermore, Lofgren said he does not consider being transgender an immutable characteristic because people’s gender identities can change over time.

Lofgren also dismissed another of the plaintiffs’ key arguments: that the health care law discriminates based on transgender status.

The plaintiffs argued the law is a form of sex discrimination because it bars minors with gender dysphoria from accessing medical treatments that are otherwise available to kids to treat other medical conditions.

Lofgren concluded the law discriminates only based on age and the purpose of the medical treatment in question.

The U.S. Supreme Court in June came to a similar conclusion in its decision upholding a ban on gender affirming care for minors in Tennessee, which Lofgren cited frequently in his opinion.

The plaintiffs also said the North Dakota law infringes on North Dakotans’ rights to autonomy and self-determination, though Lofgren found that these rights do not bar the state from prohibiting certain medical procedures.

The lawsuit was brought against the state of North Dakota in 2023 by three families with transgender children and a pediatric endocrinologist. Lofgren later dismissed the families and children from the suit, finding they did not have standing to bring it. That left pediatric endocrinologist Luis Casas as the sole plaintiff.

Attorneys for the state of North Dakota argued that the law is constitutional because the state has an interest in regulating the medical profession and protecting minors.

Two transgender adolescents and their parents testified against the ban at a seven-day court trial earlier this year. They described gender-affirming care as life-saving, and said the health care law had forced them to seek treatment out of state.

Their testimony wasn’t discussed in Lofgren’s 85-page order.

Yeargain said this wasn’t surprising, given how Lofgren structured his analysis of the case.

“If the framework of this is there is no historical support for this, and transgender status is not a protected class, and this is not discrimination based on sex and so on, then a lot of those stories are not legally relevant,” Yeargain said.

Absent a finding that the law affects a protected group or restricts an important right, judges evaluate laws in a way that is “highly deferential” to lawmakers, said James Blumstein, a law professor at Vanderbilt University.

That means state legislatures generally have broad latitude to pass laws like the transgender health care ban. Under this framework, courts will let any law stand so long as that law conceivably furthers a legitimate government interest, Blumstein said.

It doesn’t have to be the most logical or effective policy, it just needs to be plausible that the law helps achieve the legislators’ goal, he added.

“The way I like to say it is, you can burn down the barn to kill the rat,” Blumstein said.

In order to have proven the law unconstitutional, the plaintiffs would have had to present overwhelming evidence that withholding gender-affirming care from transgender kids is harmful, said Blumstein.

Jess Braverman, an attorney for the plaintiffs, said this is exactly what they did.

“The evidence at trial clearly showed how hard this ban has hit North Dakota families and transgender adolescents,” Braverman told the North Dakota Monitor last week. “It’s just really disappointing that these families won’t be able to get the health care they need.”

One parent who was formerly a plaintiff in the suit said in a statement through an attorney their family is “heartbroken and angry” about the decision.

“I am proud to stand up for the rights of my family, my child, and all transgender youth and their families in North Dakota who are impacted by this harmful law,” said the parent, who was

anonymous in the lawsuit.

North Dakota Attorney General Drew Wrigley in a statement last week applauded Lofgren’s ruling.

“The district court’s thorough and thoughtful decision makes clear that our elected legislative body appropriately reached this medical health determination and passed legislation that is constitutionally sound,” Wrigley said.

Legal advocacy group Gender Justice, which is representing the plaintiffs, said Friday they had not yet made a decision about whether to appeal.

The evidence

Attorneys for the plaintiffs repeatedly pointed out that mainstream medical associations in America endorse puberty blockers and hormone therapy as a safe and effective way to treat gender dysphoria.

Their witnesses — which included two transgender adolescents and parents, two pediatric endocrinologists, a psychiatrist and psychologist that have treat adolescents with gender dysphoria and other medical experts — said gender-affirming care can be life-saving.

The state’s expert witnesses included two endocrinologists, a psychologist and a psychiatrist. Only one of the state’s witnesses had experience diagnosing people with gender dysphoria.

They testified that there is no robust long-term research exploring the effects of puberty blockers and hormone therapy on minors with gender dysphoria, so minors and their families cannot meaningfully be informed of the benefits or risks of the treatment.

The plaintiffs’ witnesses did not dispute the lack of research, but noted it is difficult to conduct top-tier studies like randomized control trials on children because it’s unethical and expensive. They said that the existing data on gender-affirming care demonstrates it works. They also argued that many mainstream medications have been accepted as safe for use on children without this level of clinical research.

Some witnesses for the state also have had the credibility of their testimony disputed in other lawsuits.

The state’s witnesses did not deny that their views were considered fringe in the United States. However, they argued that leading medical associations only endorse gender-affirming care as safe for minors for political reasons.

It was up to the judge to decide whether the evidence indicated the Legislature had a rational basis for passing the health care ban.

Yeargain said that ordinarily in cases like this, judges will defer to lawmakers and are “not involved in the enterprise of really weighing evidence.”

“I don’t necessarily think just as a flat matter that whatever any medical association says automatically should determine the scope of legislation,” Yeargain noted. “On the other hand, I think there’s something to be said when virtually all of the major medical associations that have expertise in these areas and are qualified to opine on them pretty much articulate the same thing.”

Blumstein said he does not consider it concerning that North Dakota lawmakers adopted a policy that goes against the medical establishment.

He said the United States is in a period of transferring political power from institutional experts to elected officials.

“There was a realization that experts are not politically accountable, and having politics in the decision is not a bad thing, it builds accountability,” he said.

Comments